Cronenberg's ‘Crash’ and the violent limits between pain and pleasure

'Crash' pushed sexual boundaries decades ago, but today it stands as a clinical look at the way we come to terms with trauma.

Until 2004, there was just one Crash, David Cronenberg’s adaptation of J.G. Ballard’s novel of the same name about a group of people who developed a new definition for the term “auto erotic.” Although it didn’t win the Oscars that Paul Haggis’ film did, the 1996 Cannes Film Festival jury gave it a special prize “for originality, daring and audacity,” and yet, almost 25 years later it’s the less infamous of the two, at least among cinephiles. It also dared to explore sexual taboos that Roger Ebert would insist “in fact, no one has,” estranged Fine Line Features from Ted Turner, CEO of the distributor’s parent company, and prompted bans in Norway, the UK and from select exhibitors in the US.

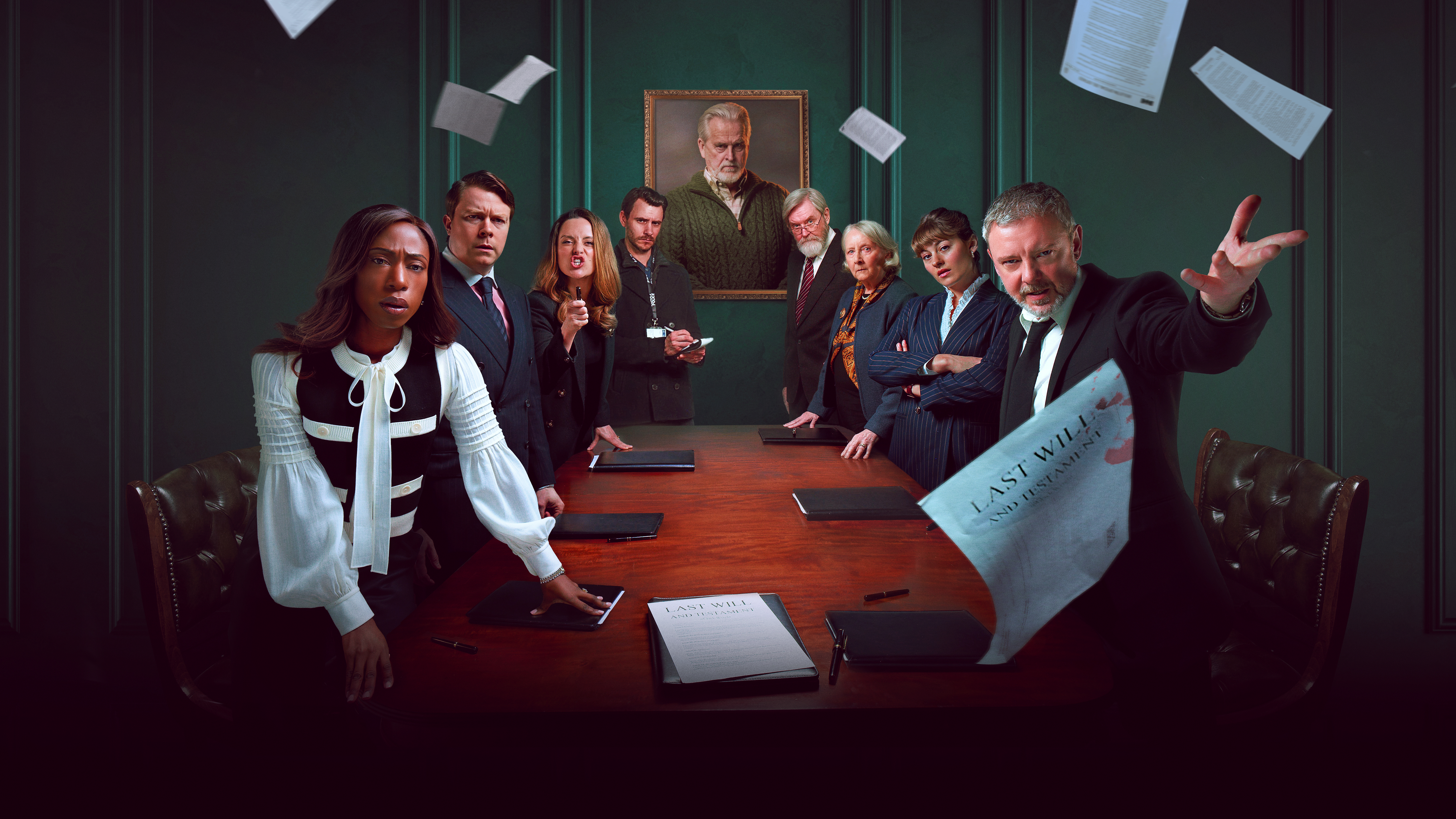

Arriving on Blu-ray for the first time in December courtesy Criterion Collection, Crash carries the imprint of a movie that couldn’t possibly be as controversial as its reputation suggests — could it? Well, certainly if you’ve ever seen Cronenberg as his freest and most unleashed, you can probably guess the answer. But revisiting the film for an overdue appraisal at a decidedly different time in cinematic and cultural history, Crash feels even more transgressive today than upon its initial release, an examination of the way that individuals process their pain and their grief, filtered for better or worse through a story with sexuality that manages to be simultaneously alarmingly graphic and unremittingly clinical.

The ‘90s, of course, was a decade dominated by erotic thrillers — Basic Instinct, Sliver, Color of Night, and dozens of copycats and their hundreds of straight-to-home-video counterparts. Adrian Lyne’s 9 ½ Weeks had already broached the subject of food and sex back in 1986, but these new films gingerly explored light (and sometimes not so light) bondage, voyeurism, and the ways that lovers test the limits between pain and pleasure. J.G. Ballard’s 1973 novel had already encountered controversy upon its publication after daring to contemplate the idea that people found automobile accidents erotic, but Cronenberg’s adaptation would bring that experience to life, perhaps dangerously so — hence the outrage from Turner and other critics. But if the film was not quite as progressive as Steven Shainberg’s Secretary six years later, which posed that dominant-submissive relationships could be fulfilling, and even loving, Cronenberg does something which few of his counterparts had done with their sexual explorations — namely, make us understand the characters’ fetishes, without trying to make us share them.

In retrospect, the film is slightly too po-faced for its own good; Cronenberg misses a bit of an opportunity to highlight undeniable truths beneath the extreme specificity of his subject matter by refusing to leaven it with a little more gallows humor, especially once its proponents are dying while wearing “big, Jayne Mansfield tits” with a chihuahua accompanying them in the back seat. But the idea of the film works effortlessly, first to disturb audiences, and then persist long enough for them to start wondering if it’s something they could accept, much less get into. This is not a movie arguing that it is actually erotic to watch or participate in automobile accidents; it’s following a growing community of individuals who have transformed their physical and emotional pain into something they can comprehend, and asking if audiences can do the same.

It starts with an accident between James Ballard (James Spader) and Dr. Helen Remington (Holly Hunter) where her husband is killed and both of them are left permanently disabled. Ballard’s open marriage with his wife Catherine (Deborah Kara Unger) is struggling to find its own erotic charge in between tales of their individual dalliances. But after seeing Remington’s exposed breast during the wreck — and then later consummating their mutual grief in a tryst in his rental car — Ballard and Remington become fixated on figuring out why the prospect of a vehicular collision gives them such an erotic charge. Their curiosity leads them to the doorstep of Bob Vaughan (Elias Koteas), a celebrity accident “reenactor” who develops a philosophy built around the belief that crashes hold a psychopathic energy drawing individuals inexorably — and fatally — toward them.

The fact that this exploration is framed by what appears to be a successful albeit unconventional marriage gives Crash its throughline, and its power. James and Catherine relay their sexual experiences to one another not only to test and explore their own appetites but to understand and satisfy their partner, so when James discovers a new source of arousal, triggered by his disorientation during the accident, Catherine tries to follow him down a path defined by pain. Together, they explore this new sexual arena as a way to become closer; it combats James’ increasing anxiety over traffic and safety, but does not alleviate it. Sex was a cornerstone and a way of coping with his life before, and now it’s become a way of sorting through the wreckage of this traumatic event. Catherine, meanwhile, didn’t have a similar near-death experience, so she can only play along (if earnestly so) and try to evoke or recreate the sensation combining that danger and eroticism.

Like James, Catherine’s path leads her to Vaughan as he becomes a prophet and advocate for this odd lifestyle, but what he’s exorcising is not the same — not even the same as James and Helen. His sexualization of car crashes is a manifestation of wanting to experience and inflict pain, where theirs reflects a way to control those elements; so when he and Catherine have sex in the back seat of his car, the experience is uncomfortable, even violent for her, as she consents. What James and Catherine eventually arrive at is a silent disharmony as he is pushed towards more violent, more terrifying encounters to unlock that sexual energy, and she follows without fully understanding, or being able to achieve it herself. Just like she encourages him “maybe the next one” after he’s interrupted early on during a tryst, he repeats these words of comfort late in the film after he runs her off the road, the two seeking sexual catharsis that likely only exists on the other side of unimaginable pain.

Get the What to Watch Newsletter

The latest updates, reviews and unmissable series to watch and more!

In 2020, decidedly more liberal attitudes persist about individual desires, but it’s hard to think that even now this is something that people should subscribe to, or explore. There’s simply too much ingrained pain and trauma to look at this outlet as healthy, especially since so much of it is about re-experiencing that sensation over and over. But for better or worse, Ballard’s story (and Cronenberg’s film of it) is indicative of the unexpected and not always healthy ways that we address and try to accommodate the experiences we have in our lives — and that as an idea is something that movies do not do often or well enough. If this movie’s nonstop nudity and interchangeable sex partners doesn’t turn you on, it’s not meant to. And so, Crash remains one of the most unique and powerful portraits ever made — not about sex, but about trauma — which may be why it’s such a hard film to approach head-on, even 24 years later.

Todd Gilchrist is a Los Angeles-based film critic and entertainment journalist with more than 20 years’ experience for dozens of print and online outlets, including Variety, The Hollywood Reporter, Entertainment Weekly and Fangoria. An obsessive soundtrack collector, sneaker aficionado and member of the Los Angeles Film Critics Association, Todd currently lives in Silverlake, California with his amazing wife Julie, two cats Beatrix and Biscuit, and several thousand books, vinyl records and Blu-rays.