Unlocking ‘The Cell’ with director Tarsem and screenwriter Mark Protosevich

The collaborators look back on filmmaking lessons learned: “when you have a body part that people are gonna look at, don't hide references!”

Arriving almost at the halfway point between the Oscar-winning beginning of the serial killer boom (Jonathan Demme’s Silence of the Lambs) and its skillful implosion (David Fincher’s Zodiac), The Cell seemed to encapsulate all of the elements that made the commercial subgenre riveting to audiences: a villain (played by Vincent D’Onofrio) whose personality was as twisted and fascinating as the determination and goodness of the women (Jennifer Lopez) and men (Vince Vaughn) trying to stop him, a ticking clock counting down towards an unimaginable fate for a poor young victim, and striking, singular imagery designed alternately to mesmerize and terrify.

First-time screenwriter Mark Protosevich (I Am Legend) built a troubled, tragic, violent back story for D’Onofrio’s Carl Stargher, which first-time director Tarsem (The Fall) breathed to terrifying but often beautiful life on screen. The film’s distributor, New Line, gave the duo wildly uncommon freedom to adapt and reimagine their story on the fly, creating a film that touched on dozens of artistic, literary and scientific references, but whose final look feels unlike anything else in the heavily-populated and frequently derivative canon of cinematic serial killers.

“I didn't think for the life of me I would do a serial killer film,” Tarsem tells What To Watch. But when this came along, I said, if you think this is going to look like Seven or Silence of Lambs, you're on a different planet. This is a Hindi movie, and I'm going to get in there and I'm just going to go and go opera with it. You had to have a different take. That was just a shell that greenlit it.”

Celebrating the film’s endurance, and uniqueness, 20 years after it was originally released, Tarsem and screenwriter Mark Protosevich spoke recently to What To Watch in lengthy interviews recounting their experiences making The Cell. They discuss the complex foundations for the scientific process used to explore their (fictional) deranged mind, the casting and collaborative decisions made to render its real and psychological backdrops in vivid, unforgettable detail, and the odd, funny and unexpected discoveries and life lessons learned along the way.

What was your original impetus for The Cell, particularly at a point where serial killer movies were a booming commercial subgenre?

Mark Protosevich: I was interested in the extremes of psychology and the extremes of human behavior and the serial killer is this fascinating character in our world. My intention was to try to put a unique spin on the genre in that technically the killer is captured very early on in the story, and it's less about his methodology and more about his mind. And one of the things that did crop up in a lot of my research about various serial killers was the effect on many of them, of childhood trauma. So I was curious to see if there was some way to show the humanity of a person who's capable of these kind of terrible crimes. Is there a human being in there somewhere, or are they purely evil? So that idea was interesting to me, to try to get into the head and the heart of someone who does really awful things. And I'm not saying that someone who commits these terrible murders should be looked at with sympathy, but I just personally found it fascinating to toy with the idea of perhaps finding some part of them that we could connect with on a human level.

Tarsem: I had no interest in a movie. I had this personal film I was going to do first. But when this thing came along, it happened much faster than I thought, and I just said, okay, let's just do it. It's in position and everything is there. And then I went after that for The Fall. But I was not looking for a movie.

The latest updates, reviews and unmissable series to watch and more!

Protosevich: Everyone who read the script felt it was a real page turner, and I definitely wanted it to have that quality. So the core structure was always there, building toward finding the last victim and gaining information from inside the killer's head definitely led them to her rescue. But the key factor was building toward Catherine bringing the killer into her mind. That in the original drafts was quite different in that she confronted him about his crimes. There was a scene where his victims were alive in that world with her too, and he had to confront them as real people whose lives he took. But building up to that moment of him coming into her world and her being in control and being dominant was always going to be the really juicy part of the story for me.

Tarsem: The first thing I told them is, “are you open that all that's written in there goes away?” They said yes, so I said give me the amount of money and suggested to Mark, just write three lines and leave seven pages blank, so they know it's not three lines. Literally I told him, all you have to do is just write only what happens - she goes in, she finds this, she gets scared. This thing happened, that thing happened. And then the creative team gets in and I'll put these scenarios out, but they still won't be locked. So I made a nutshell and he was fantastic in accommodating all of that and putting it in. And this is while we are about to make the movie - it was green lit with what he had!

How many of the artistic and literary references in the film were written into the script?

Protosevich: I have been told that when people read a script of mine, they can very clearly picture the movie in their head. But the visual aspect of those dream sequences are very much him. When she first meets his victims in his mind, I described it visually as Nine Inch Nails meets the brides of Dracula, and there was some specific imagery of the dog and the childhood abuse and going to his family home. But the specifics of those visuals, Tarsem uses a lot reference material. He had an assistant who just scoured art books for source ideas. I remember when the film came out, Time magazine did a comparison of certain works of art and certain scenes in the movie, pointing the direct references. But that was very conscious and Tarsem, it was very clear that he was using certain things as inspiration, but other aspects of it were very much him.

Tarsem: They had a reference, and I thought they would pay off in the end when [Detective Novak] goes into Stargher’s room and you would see where he got them from. There was only one reference I almost had to give up: they said you can't cut the horse. They said Damien Hirst basically has lawyers that sue people and that's how he makes money. And I said, “but do you know where Damien Hirst got it from?” and I showed them the card from the Natural History Museum where they did it with formaldehyde and a shark, but that was 60 years ago. The lawyer wrote back to me and said, “we encourage him to come after us.” The quote is "originality is the art of concealing your source." But everything passed. So we had all these references and I took Mark's dots and I simply connected them. He told me, “there's these girls in [his head] and they're victims.”

Mark Romanek, my friend, had done the Nine Inch Nails video, and the art director was the same as our film. I said, “make it like that, but it looks like when you go to the Natural History Museum and they have dioramas.” So you see a whole bunch of references that don't make sense and then you tie them [together] in the end, which is what you get in The Cell. But a lot of things, you kind of pepper them in and they come out later. Like if she's going on a horse when she goes to see the guy, she goes to the fridge to pick up something and there's a picture of a horse that's in the back of the exact style that she's been riding so she's used it in her psyche. The problem was, she sits down in her underwear to pick up milk for the cat, and nobody looks at anything else except J.Lo's butt, so nobody sees that reference. And I learned, when you have a body part that people are gonna look at, don't hide references! Nobody's going to see it unless they freeze the frame.

How did Jennifer Lopez get chosen as Catherine?

Tarsem: There was a very smart movie in the [original script] that could have been made, but couldn't get greenlit. And the only person I met about [that version] was Julianne Moore. I was going to mix Ken Russell in there. These guys are doing drugs in a fucking lab and they hang themselves like La Jetee in hammocks where basically they're having a common hallucination. But the drug isn't strong enough. They can only do it with people who are in a coma. So the FBI has this guy and they've got three or four days and they go in a drug induced thing like Altered States, and come out from that. Julianne Moore loved it. And every studio said, “great. You want to make that movie? The budget's like $10.”

Protosevich: I was told that that Julianne Moore very much wanted to do it, and she was who I saw in the movie when I wrote it, that type - Julianne Moore kind of projects this maturity and intelligence and toughness.

Tarsem: What the studio was talking about was doing this with what we would call in Bollywood a diva. I said, “oh, like Jennifer Lopez.” They said, yes! I said, no, I mean like [Jennifer Lopez]. They said, yes, her! I said, okay, so just say anybody like that who is not what you would consider a doctor to be, but you'd go into this particular world [with]. And then in the testing, people were critiquing J.Lo as a shrink. But my idea was, if you’ll come to see a movie with J.Lo as a shrink, have I got a fucking movie for you! So if you're coming to see a movie where you don't buy J.Lo as a shrink, then you're in the wrong movie. It worked out magically.

Protosevich: Jennifer Lopez at the time was very young still, so we had to make some adjustments. She became someone who was just starting out in her career as opposed to someone who was very established. There's a vulnerability to her, but her strength is this great empathy and her kindness. I think she did a wonderful job.

What led to using Eiko Ishioka as your costume designer?

Tarsem: Earlier I wanted it to be an action flick inside the head, and when The Matrix came out, they said, you can have [that technology]. And I said, no, now everybody with two dollars in their pocket is doing those stunts. I want to do opera. And they said, that’s not what Americans like. One of my favorite films was Dracula, which is essentially opera. And that’s a prime example of a movie that opened at about $35 million but didn't make a hundred million, which means people want to see this movie, but not that movie. So they told me Americans don't go to opera. But this film is actually serial killer shit that everybody wants, so give me Eiko Ishioka’s clothes, that’s the Trojan horse, now let me put the stuff inside it. And they let me go with it. Hats off to people like Mike De Luca and all those people who let it happen. Then in the last act when D'Onofrio is there and Catherine is supposed to fight Stargher, Eiko, who I adored and loved, came up with this massive cloak and it took three guys to hold it on him. And Eiko's like, “does he have to fight guys?” And it said three pages [of fighting]! So I said, I'll tell you what. He comes out of the little lake and he goes, boom, show the cape, and now he can fight. And then Catherine shoots him in the foot, comes up and pulls [a piercing off of his chest]. And then she goes and drowns his inner child. And they kept letting us make it up.

What discussions occurred about portraying the film’s themes, which include a lot of sexual dysfunction and brutality?

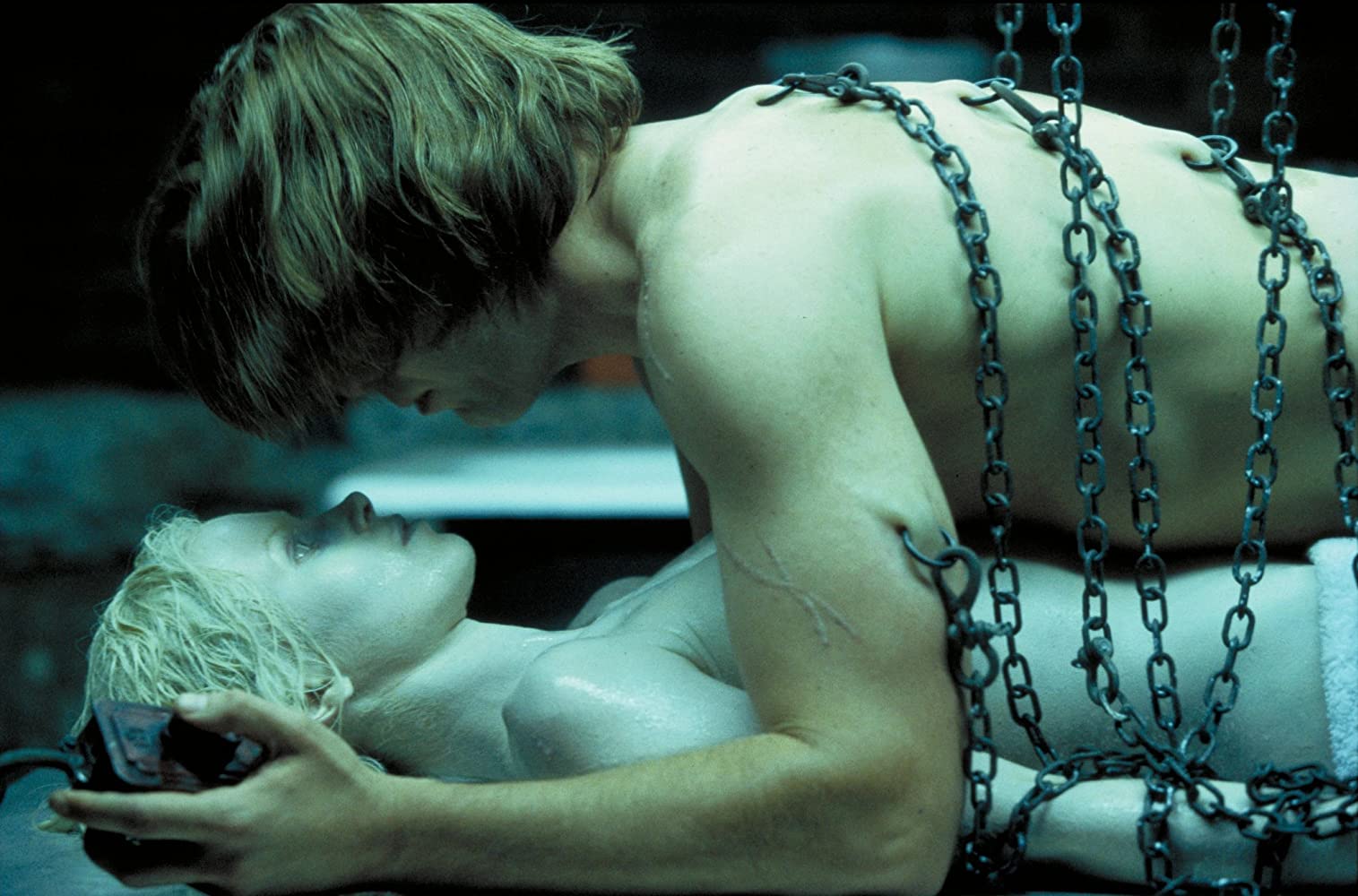

Protosevich: The scenes in the cell itself were even better than I could've imagined. It looked like it would work. I had an idea of what the dream sequences and Stargher’s world would be like in my head, and what Tarsem did really, he brought something so unique and visually strong to it that did stuff that I never even thought of. There are certain scenes in there that were entirely his invention - the pierced rings in Vincent D’Onofrio’s back and the hoist and him masturbating above the bodies. The methodology in the original script was much different. In the very first drafts, he tattooed his victims with these very unusual tattoos. And then the intestinal torture scene of Novak, based on that painting that they eventually find, Tarsem had these very, very specific visual things he wanted to create. When I saw them, I said, Oh my God, this is stranger and wilder and more beautiful than I could have imagined.

Tarsem: De Luca told me in the very beginning, “I want a disturbing film.” And I was like, you got it, guy. I remember when I showed the rough cut and he said you’ve got to cut stuff out, I said, you said you wanted a disturbing film! But everybody has a different level of what they can take. And everybody had something they wanted out of the movie. The studio thing was “take out the wanking,” the masturbation from the film, and the American version that you see is a smaller version. But the Germans called me and said, “you got any more wanking we can put in?” So the European version is slightly longer there. But everybody had a breaking point and I was just trying to find it. Mark's was very strange. It was when I said, “she goes in and a horse gets [vivisected].” He said, “you can't do that.” But I was like, “you're abusing a child here. What's up with this?” And then I met him at his farm and of course, he has horses. So it stayed in.

Protosevich: The big question that I had to ask myself and then Tarsem had to ask was what would the interior fantasy world of a serial killer look like? And that's a pretty scary thought. You read a lot about the psychology of a serial killer and a lot of it is that they see themselves as a kind of God, an all-powerful, controlling figure. But I wanted to contrast the idealized version of himself in his imagination [with] the other aspect of seeing yourself as a vulnerable child. So the dream sequences were more about contrasting these different sides that lurk in our unconscious. And Tarsem definitely brought very specific ideas about how to treat it visually.

Tarsem: For that suspender scene, I wanted just a close-up. But Vincent D’Onofrio wanted to make sure that it could actually hold his weight, so he went up - and he got a head rush. He passed out, and I said bring him down, I'm doing a close up. For a person like that, you just go, what does it take for you to bring that [performance], and he said, “get me in there.”

How difficult was it to nail down the right tone for the story, since the costumes and setting were often so exaggerated?

Tarsem: Everybody had a particular point that I was trying to trigger, and I remember the clothes were looking so ridiculous with Eiko - and I loved that. And they said, if you go with that that they laugh - they call it a bad laugh, when people laugh at you, not with you. And they said this is going to be laughed at, a guy wearing a skirt. I said, I'll come up with something upfront that he does that is so disturbing that in the third act he could come out wearing a sari and a fucking tutu, and nobody's going to laugh at him. So then me and Eiko would sit down and say, okay, what does this guy do? He drowns the girls. He masturbates with them. So we fucked him up so bad so that in the first act that by the time those things came, you're like, I don't want to laugh at this guy.

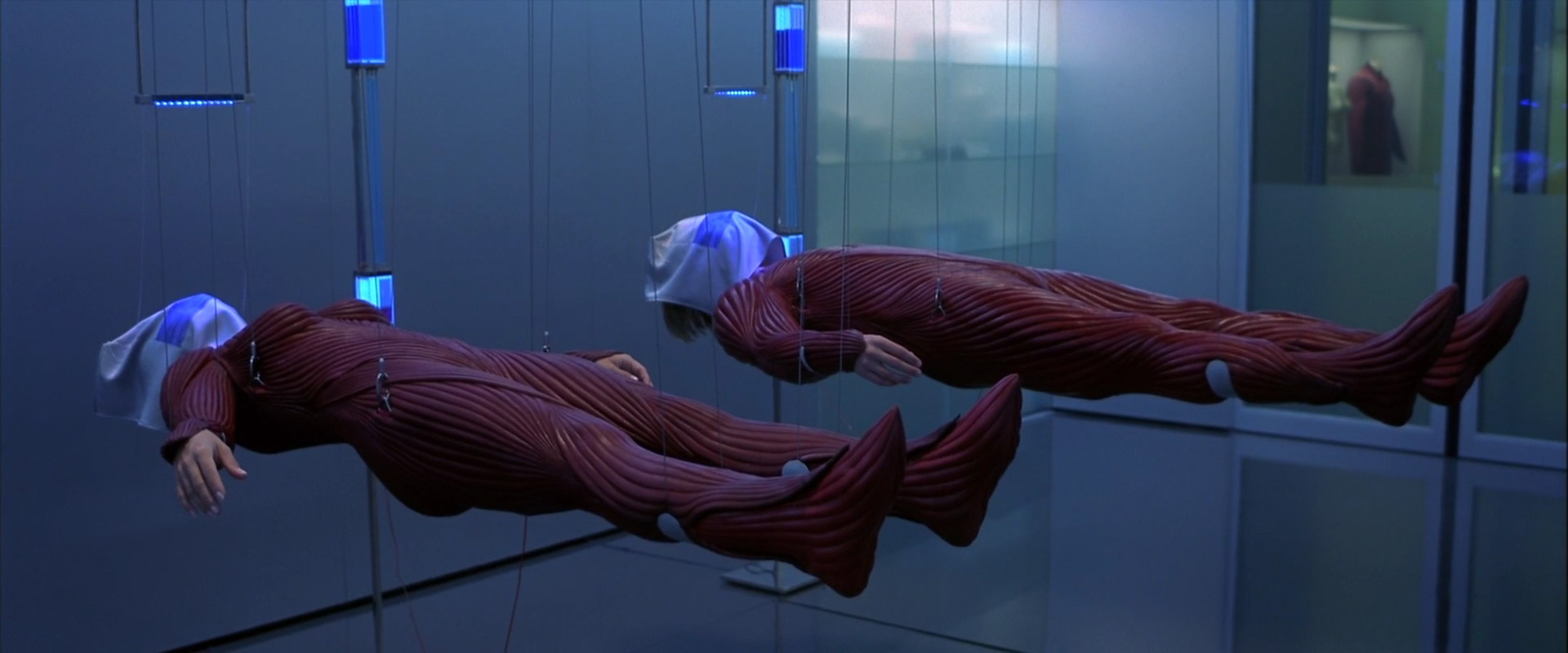

Eiko Ishioka’s costumes are extraordinary. They make sense in Stargher’s mind, but why was it important to feature the “muscle suits” in the real world?

Tarsem: Very, very well spotted. They should belong in the fantasy. I'd seen this film and it really freaked me out called Coma in which these people in comas are suspended with wires, so I just said “suspend them.” Then everybody asked, why are you suspending them? And the main thing that happened with Stargher has got to do with water. So I had to bury those messages in the film - the first time he had a shock was during a baptism, Catherine is sleeping in the beginning in a waterbed, so somehow that whole thing leads you into this particular dream state. Instead of lying down, you need to be suspended like you're in water. And Eiko had done this suit similar to the warrior suit she had done in Dracula - and there, it looks good, just for the sake of looking good. But for this I told Eiko, “go for a muscle suit like you've taken the skin off and they're leaving this world behind.” And everybody was quite right that it belongs in the other world. That's a director's wank. I just said, it looks fucking great and we've got to put it in. And you know what, it smelled - whatever she did, the chemical thing was horrible, and J.Lo hated it. That's why you never see her standing. The one time she stands, I had to shoot in close-ups and wides because the shape that it gave her, she looked like a pear. It was horrible. But it worked.

What battles if any did you have with the studio to preserve all of the wild ideas you injected into what was supposed to be a straightforward serial killer movie?

Tarsem: I remember we showed it to the head of the studio, Bob Shaye. He saw it, and the music's not done and the effects are not done, and you're asking people to come in and give you notes. And I said, why don't we give them a script? If it's a visual piece, let the visuals speak! They go, “no, they're just using it as a guide.” They say all that, but it's an unfinished thing. It didn't look very good. They're testing it - and of course the numbers are horrendous. And Bob Shaye said to me, “I know what will solve this. I'll show you a film that we did that was very successful.” The first Nightmare on Elm Street is one of my favorite films - but he sent me Part 4 [The Dream Master]. I watched that film, and I put it up on the editing board for everybody walking in. I said, “guys, don't worry, because the studio thinks this is the movie we have to beat.”

What reflections do you have about the making of The Cell, and what lessons did you learn from the experience of making this that you took forward to the subsequent movies that you've made?

Tarsem: It was a movie that they might have buried. And I think eight days before, they realized it's going to be big, and then suddenly they were throwing money at it to advertise it. They were trying to throw everything in, and I was in those stupid days when you're idealistic and if they changed things, I’d think "how dare you?" The guy who did [the theatrical] trailer changed two shots and I told them, "I'm leaving the country." And I remember D'Onofrio called me. I was shooting a commercial somewhere in the East and he said, "we're at the junket here, and everybody knows it's a visual film. Why are you not here?" I said, “they changed two shots in the trailer!" And he just said, "you have a lot to learn, my friend." Then I went forward and realized they gave me all that [latitude] and I was still being a fucking dick. But I said, just let me finish the piece how I want. So the film apart from a little bit off the masturbation scene - which changed the tempo as far as I was concerned for me in the American version - I got to do what I wanted.

Protosevich: This being the first script of mine to get made really spoiled me because I’ve been writing professionally for 25 years now. But the experience I had on The Cell, I only had one other time where I was the only writer on the movie. And it's very rare. I mean, I find it incredibly satisfying and feel that that's the way it should be. But it's just not the way the business is really structured, at least the majors. It's not so much about your individual vision. It's about what's going to best serve the material. And that's fine. I always use this analogy that screenwriters are like baseball pitchers, and some people are starters and some are relievers, some people are closers. like if you come in and rewrite somebody, you're relieving them so to speak, or if you're the guy on the set, you're the closer. And I'm a starter. I like being the first person on a project. I'd rather be the first person involved, and I have this naive hope every time that I'm going to pitch the entire game, that I'm going to pitch on all nine innings and they're not going to want to take me out. Most of the time, you're taken out in the sixth inning or whatever, and that's just the nature of the beast. When it doesn't happen, it's fantastic. I love being as involved as I possibly can.

Tarsem: When I came from [the world of music videos], it was a complete world that I controlled, and people won't believe it, but when I did the advertising that I did, I would also get to exactly what I wanted. This was the first project that I was doing when the c-word crept in - by that, I mean compromise. Literally when I went in there, I realized like, what? J. Lo's not going to wear the wig that I want? That was news to me. And I was flailing. And later I realized how much more I had than the average person has when they make a film. I should've been a lot more grateful. But also, I don't think we would have ended up with the film that we ended up with. You needed a dick to say, no, you're not going to change that. Otherwise I might not have been able to drown the child. I might not have ended up with the skin suits.

Protosevich: When the movie came out, it had its admirers, but it also had a lot of detractors. I think a lot of people wrote it off as just another serial killer movie, or they called it what used to be called “like an MTV video.” I really love that it has developed a really strong cult following. I really do feel in a lot of ways it was ahead of its time. Because I think if it came out today, I think the reaction would be different. It definitely was fairly successful. And it did have its admirers, most notably Roger Ebert, who just loved it. But I'm glad that now it really seems to have a lot of support. And it still holds up for me.

Todd Gilchrist is a Los Angeles-based film critic and entertainment journalist with more than 20 years’ experience for dozens of print and online outlets, including Variety, The Hollywood Reporter, Entertainment Weekly and Fangoria. An obsessive soundtrack collector, sneaker aficionado and member of the Los Angeles Film Critics Association, Todd currently lives in Silverlake, California with his amazing wife Julie, two cats Beatrix and Biscuit, and several thousand books, vinyl records and Blu-rays.