What to Watch Verdict

'Louis Wain' goes through the motions of a standard biopic with only an occasional acknowledgment that a distinctive life probably deserves more artistic flair in its presentation.

Pros

- +

Occasional bouts of whimsy break up the monotony

Cons

- -

A dour, miserable story with about as much depth as a Wikipedia summary

- -

The film seems disinterested in Wain's internal life beyond his continual suffering

- -

Cumberbatch's performance is practically a parody of itself

It’s not hard to see what the appeal in pitching a film like The Electrical Life of Louis Wain must be. Wain was an eccentric figure in his life at the tail end of the 19th century, celebrated for his increasingly surreal paintings and drawings of cats that helped to popularize felines as an English pet of choice, rather than just tolerated rodent-catchers. But a faithful telling of Wain’s life needs to grapple with the fact that his world was largely defined by his relationship with tragedy and trauma, so any exploration of the apparent whimsy in his work would necessarily bump heads with the bitter realities that he seemed incapable of fully processing. Unfortunately, despite best efforts, The Electrical Life of Louis Wain never rises to the task, failing to conduct more than a few sparks of inspiration between bouts of dire misery.

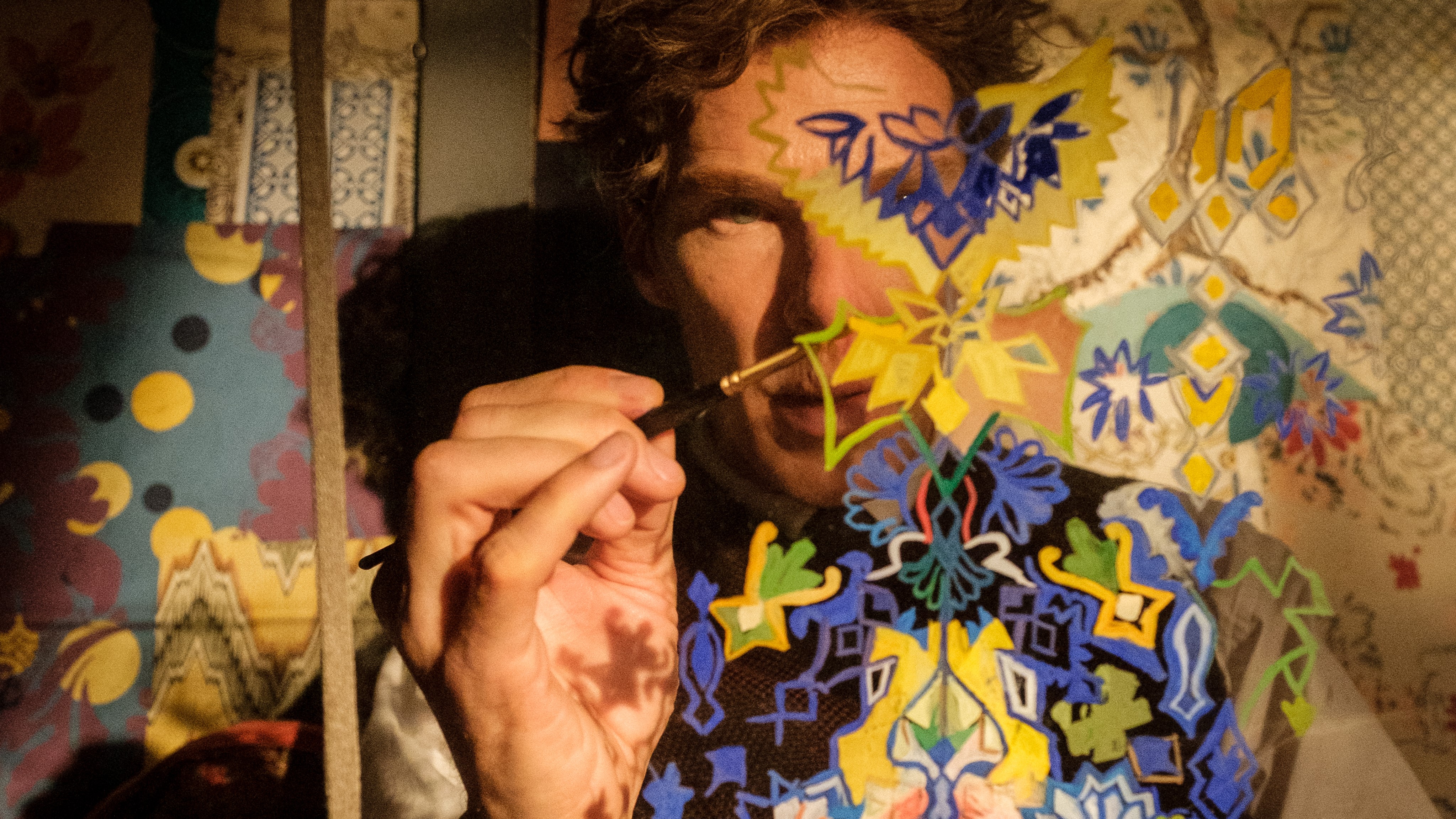

Much of this comes down to the portrayal of Wain himself, leaning on Benedict Cumberbatch’s recurring penchant for playing neurodiverse Englishmen, here almost to self-parody. As breadwinner for his ailing mother and five sisters — the eldest of which is played by Andrea Riseborough with just enough dimension to prevent her from being a one-dimensional nag — Wain’s attentions shift wildly between sketching animals, formulating pseudoscientific theories about the relationship of life to electricity, boxing and his nightmarish fixation with drowning at sea.

The only person capable of seeing past his nervous tics and special interests is the governess of his younger sisters, Emily Richardson (Claire Foy), whom his affections for are the only reason he retains a job as a newspaper illustrator. As capable as Foy and Riseborough are as sympathetic and frustrated foils to Cumberbatch’s rambling, mumbling, fumbling performance, they contribute to a continually muted tone that Cumberbatch is constantly trying to break away from, as if the film might flatten out into a cartoon at any moment were it not for the women in his life constantly insisting on reality.

But one soon comes to realize that the consistent grounding of the narrative, the continual pull back to a recognizable realism, is mainly done in reverence to a constant sense of tragedy that pervades Wain’s life. His marriage to Emily is cut short by a bout with cancer, which in turn sets off his career-defining fascination with cats in remembrance of the kitten the couple adopted together. The emphasis on his life’s tragedies only escalates from there, but it inversely makes Wain’s character more alien and less comprehensible as a real person. The film is so entirely unconcerned with Wain’s humanity beyond his eclectic interests that it completely neglects to provide us more of a window into Wain’s character other than to say that great art arises from pain, an observation so pat and overexplored that it’s a shame there’s nothing more for the film to hang its hat on.

It’s so bizarre, then, to see glimmers of inspiration here and there, to see glimpses of a film that can at least take the smatterings of its shallow conception and stylize them into the facsimile of substance. The choice to cast Olivia Colman as the film’s matronly storytime narrator is bizarre, almost infantilizing to Wain himself, but it’s at least a choice with personality. A conversation with a fellow cat enthusiast devolves into Wain’s unhinged assertions that the electrical energy of cats will one day allow them to turn blue and stand upright, which is evidence of a much higher level of absurdity than the film is usually comfortable with. The most interesting quirk comes in the eventual introduction of subtitled meows for Wain’s many cats, including one adorable instance of a mewling kitten proclaiming “I love jomping!” Oh yes, dear reader, he does give a little jomp.

Moments like these are oases of attempted levity in a film that is otherwise a slog to endure. The Electrical Life of Louis Wain is not unwatchable, but it’s indicative of misplaced priorities in examining the life of a truly unique individual. Cumberbatch’s broad performance is nearly impenetrable as anything more than a vessel for pain and deteriorating mental capacity, which is sadly fitting for how disinterested the film is in diving deeper than that. If the real Louis Wain was truly such an enigma, surely that could have been harnessed to drive the engine of a narrative. Instead, he’s pulled along with all the inertia of a Wikipedia article, going through the motions of a standard biopic with an occasional acknowledgment that a distinctive life probably deserves more artistic flair in its presentation. But for a film that can’t even be bothered to highlight its artist’s famous works until the credits start to roll, maybe that’s too much to ask.

The Electrical Life of Louis Wain opens theatrically on Oct. 22, then on Amazon Prime on Nov. 5.

Leigh Monson has been a professional film critic and writer for six years, with bylines at Birth.Movies.Death., SlashFilm and Polygon. Attorney by day, cinephile by night and delicious snack by mid-afternoon, Leigh loves queer cinema and deconstructing genre tropes. If you like insights into recent films and love stupid puns, you can follow them on Twitter.